Every dewatering plan eventually runs into the same uncomfortable question: what happens when the suction line fills with air instead of water? If you are weighing wet prime vs dry prime pump options for a rental fleet, a bypass contingency, or a site that cannot be babysat at 2 a.m., you are really choosing how you want to manage risk. One style rewards simplicity and lower cost when conditions stay stable. The other buys you time, uptime, and automatic recovery when the job turns unpredictable.

You are not just selecting flow and head. You are selecting a priming strategy.

A wet prime pump depends on a retained water reservoir inside the casing to create vacuum and establish suction lift. It works well when your suction stays wet and your system stays tight.

A dry prime pump adds an external priming device, commonly a vacuum pump, diaphragm pump, compressor, or venturi priming arrangement, to evacuate air from the suction line and prime from a completely dry state. It is designed for automatic repriming and for staying effective when air keeps showing up.

The Priming Problem: Why Dewatering Pumps Lose Suction

Dewatering is rarely a steady-state lab condition. Your suction hose flexes, a strainer shifts, a wellpoint header gulps air, or a sump gets pulled down faster than it recharges. Any one of those events can interrupt prime.

When prime is lost, your centrifugal pump is still spinning, but it is no longer moving liquid. That creates a chain reaction: reduced cooling at the seal faces, heat buildup, and sometimes rapid mechanical seal damage.

You usually see prime loss traced back to a handful of field realities.

- Suction-side leaks

- Air entrainment at the intake

- Inadequate submergence

- Check valve problems

- Long suction runs with high points that trap air

The more your operation depends on unattended runtime and predictable discharge, the more priming becomes a reliability feature, not a startup step.

What is a Wet Prime Pump? (Standard Self-Priming)

A wet prime pump is the classic “true self-priming” centrifugal design used across construction and general dewatering. Before the first start, you manually fill the casing with water. That retained liquid forms the sealing medium that lets the impeller act like an air pump long enough to evacuate the suction line.

Inside the casing, an air separation chamber effect occurs as the pump circulates the air-water mix. Air is expelled out the discharge, and water recirculates back into the volute so the impeller stays wetted. Once the suction line fills, the pump transitions into normal centrifugal pumping.

This design is attractive because it is mechanically straightforward. With fewer auxiliary components, you usually get lower upfront cost, fast serviceability, and less specialized troubleshooting.

The tradeoff is non-negotiable: if the casing loses its retained water, wet prime behavior stops being “self-priming” in any useful sense. You are back to manual priming, and you are exposed to run-dry risk if the unit continues operating without liquid.

What is a Dry Prime Pump? (Vacuum-Assisted)

A dry prime pump, often called vacuum-assisted or priming-assisted, pairs a centrifugal pump with a dedicated air removal system. The priming system continuously pulls air out of the suction line until water arrives, then it typically throttles or cycles while the pump runs.

In practical terms, this means you can connect hoses and start the unit without filling the casing. The priming system establishes suction lift by evacuating air, drawing water up the suction, and maintaining prime even when air keeps entering. That is the core of automatic repriming.

Dry prime setups vary, but most include:

- A vacuum pump (or diaphragm/rotary vane style)

- A priming chamber with floats or valves to manage air and liquid

- Check valves to protect vacuum integrity and prevent backflow

You are paying for a system that treats air as a normal operating condition, not an exception. That matters on bypass lines with fluctuating inflow, on wellpoint headers that constantly entrain air, and on any site where staffing is limited overnight or across weekends.

The “Snore” Factor: Handling Air-Water Mixtures

On real jobs, the water level drops, the pump starts pulling air, the discharge coughs, then water surges back. Crews call that “snoring” because the pump cycles through air and water with an unmistakable sound and vibration pattern.

Snoring is not just noise. It is an indicator of how your priming method handles intermittent flow and air ingestion.

With a wet prime pump, snoring can quickly become de-priming. Once enough air accumulates and the casing water level drops away from the impeller eye, the pump can no longer sustain vacuum. You may end up dispatching someone to refill the casing, reseat a check valve, or rework suction conditions.

With a dry prime pump, snoring capability is the point. The vacuum system continues evacuating air and stabilizing the suction line. When water returns, the pump resumes moving liquid immediately without waiting for a manual re-prime. On projects where recharge rate is inconsistent, that difference shows up as fewer site visits, fewer restarts, and fewer “mystery downtime” gaps in your logs.

If you manage a rental fleet, snoring tolerance often correlates with fewer emergency callouts and better rental fleet efficiency, even if the equipment itself is more complex.

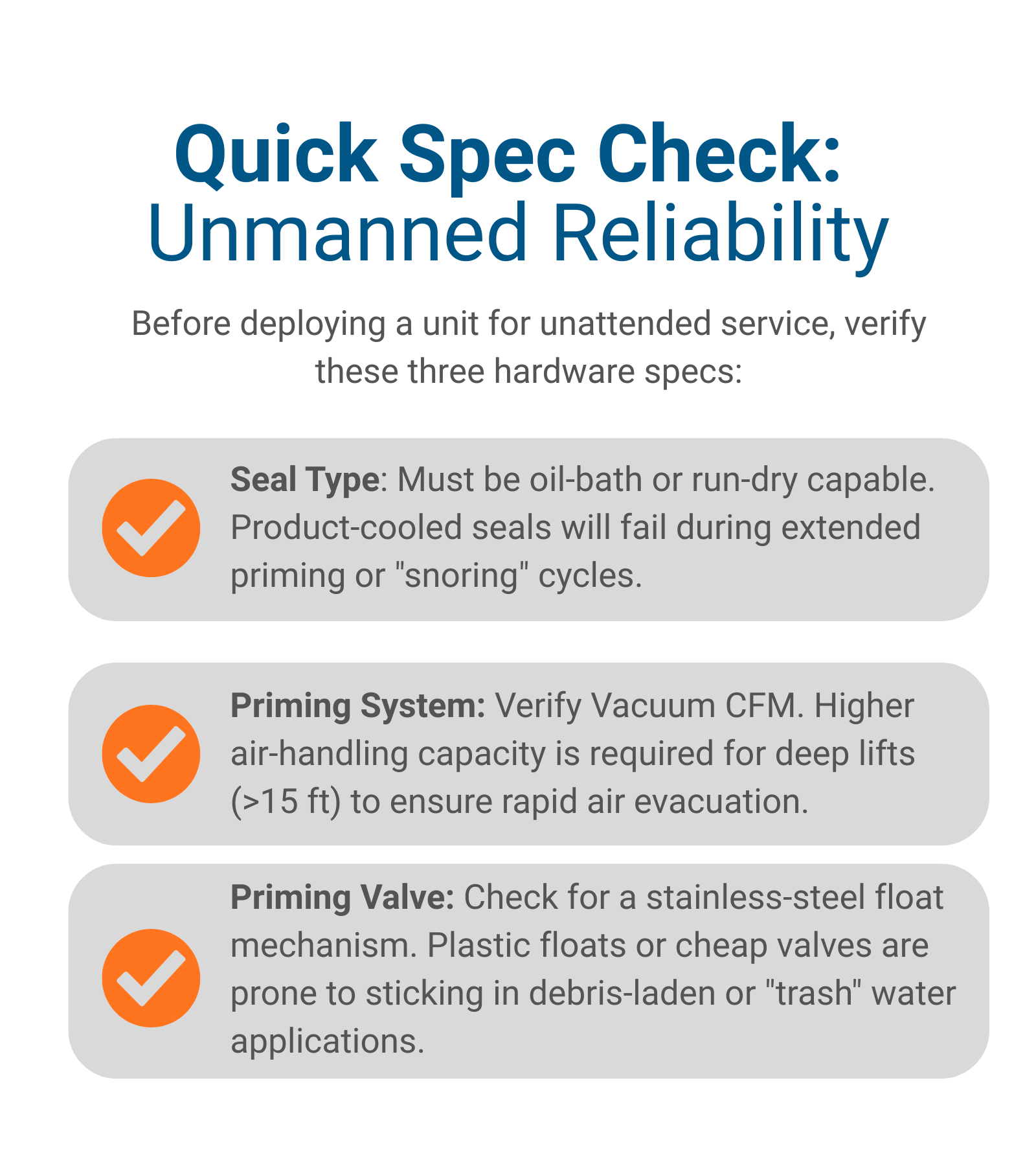

Run-Dry Capability: Saving Mechanical Seals

If you want one decision filter that resonates with superintendents, it is seal protection under low supervision.

A wet prime pump generally cannot run dry without damage. The pumped liquid cools and lubricates the mechanical seal faces. When the casing runs dry, the seal faces can overheat fast. Even brief dry operation can reduce seal life, and extended dry operation often ends with leakage and failure.

A dry prime pump is typically built around run-dry protection. Many units use an oil-bath seal system or a run-dry capable seal arrangement designed to tolerate extended air handling and priming cycles. That makes the package far better suited to unmanned operation. Your risk profile changes from “seal failure after a short incident” to “unit survives and recovers when water returns.”

If your job includes night runs, weekend spans, or restricted access sites, run-dry protection is not a premium feature. It is an insurance policy against the most common failure mode in intermittent dewatering.

Maintenance Comparison: Simplicity vs. Complexity

Wet prime units stay popular because maintenance is uncomplicated. You are maintaining a pump, a driver, and the usual wear items. Troubleshooting is also familiar: suction leaks, worn seals, clogged strainers, damaged check valves.

Dry prime units can deliver higher uptime, but they ask for more disciplined preventive care. You have added components that must stay functional for priming performance to remain reliable.

From a service planning standpoint, you are balancing fewer parts against fewer field failures.

- Wet prime maintenance focus: suction integrity, casing fill practices, check valve condition, seal temperature exposure

- Dry prime maintenance focus: vacuum pump health, belts or couplings, priming chamber cleanliness, valve/float function, vacuum line integrity

The difference is not that one is “high maintenance” and the other is “low maintenance.” The difference is where the maintenance lives. Wet prime pushes more burden into operations and monitoring. Dry prime pushes more burden into scheduled inspection of the priming system.

Quick comparison table for reliability planning

| Category | Wet Prime (Standard Self-Priming) | Dry Prime (Vacuum-Assisted) |

| First start | Requires manual casing fill | Primes from dry without adding water |

| Automatic repriming | Limited | Strong, designed-in |

| Air handling | Sensitive to air ingress | Built for air-water mixtures |

| Snoring capability | Often loses prime | Typically continues and recovers |

| Run-dry protection | Minimal | Common (oil-bath or run-dry seal systems) |

| Failure mode you see most | De-prime, seal damage | Priming system component issues |

| Best fit | Stable sumps, constant water | Variable flow, unmanned uptime-critical |

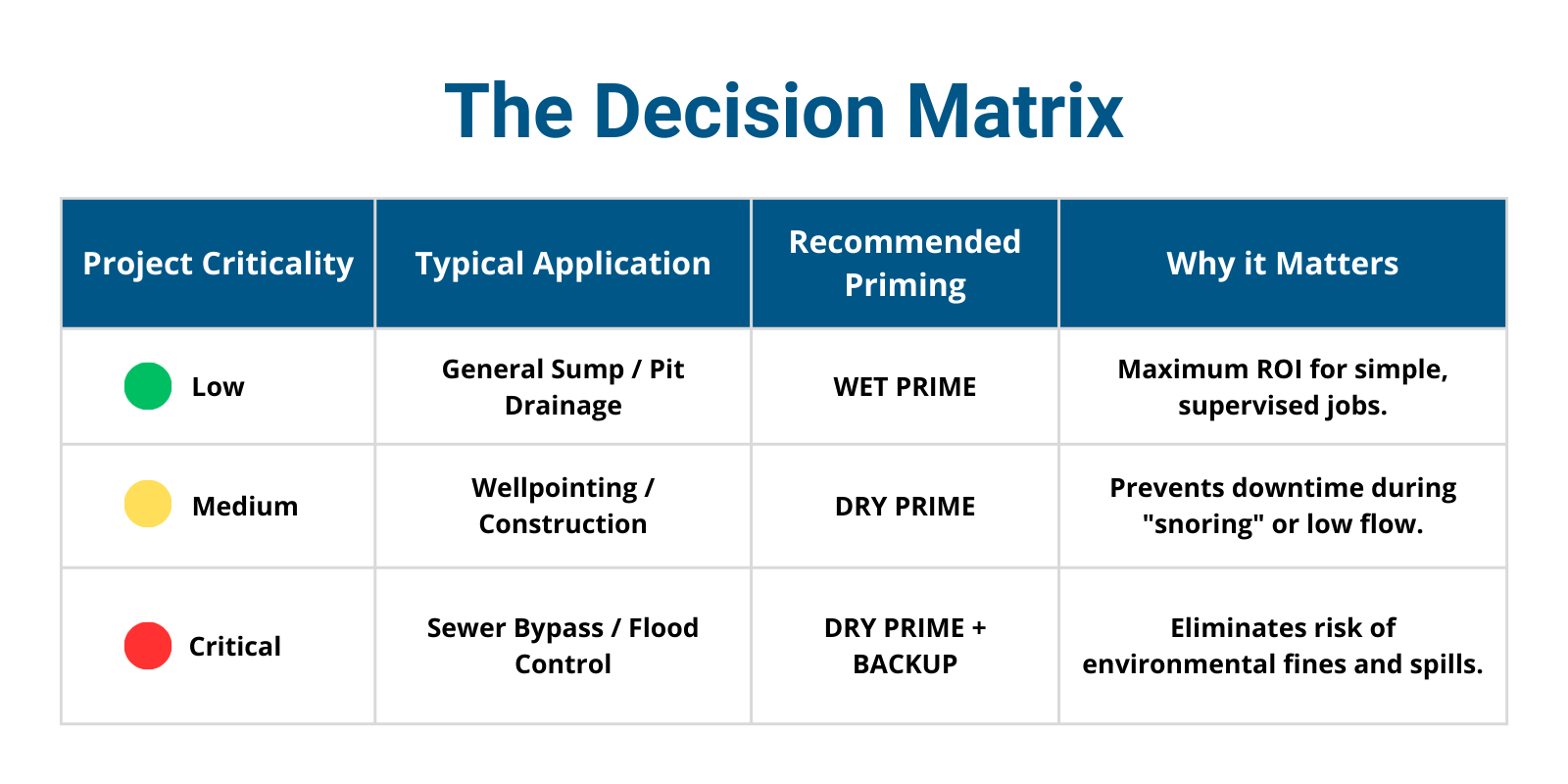

Selection Matrix: Sewer Bypass, Wellpointing, and Sumps

Your selection should start with the operational scenario, not the pump brochure. Sewer bypass and wellpointing punish weak air handling. Simple sump duty rewards simplicity.

When you map applications to priming style, a pattern shows up quickly.

- Sewer bypass: Choose dry prime when uptime is non-negotiable and any interruption risks surcharging, spills, or public impact.

- Wellpointing: Choose dry prime because the header routinely carries air, and suction conditions often change as drawdown progresses.

- Sumps and excavations: Choose wet prime when the sump stays flooded, the lift is modest, and a crew is already present to monitor conditions.

You can also sanity-check the choice using three field parameters you already track on most plans: suction lift, variability of inflow, and tolerance for interruption. If any one of those pushes into “unpredictable,” dry prime earns its keep.

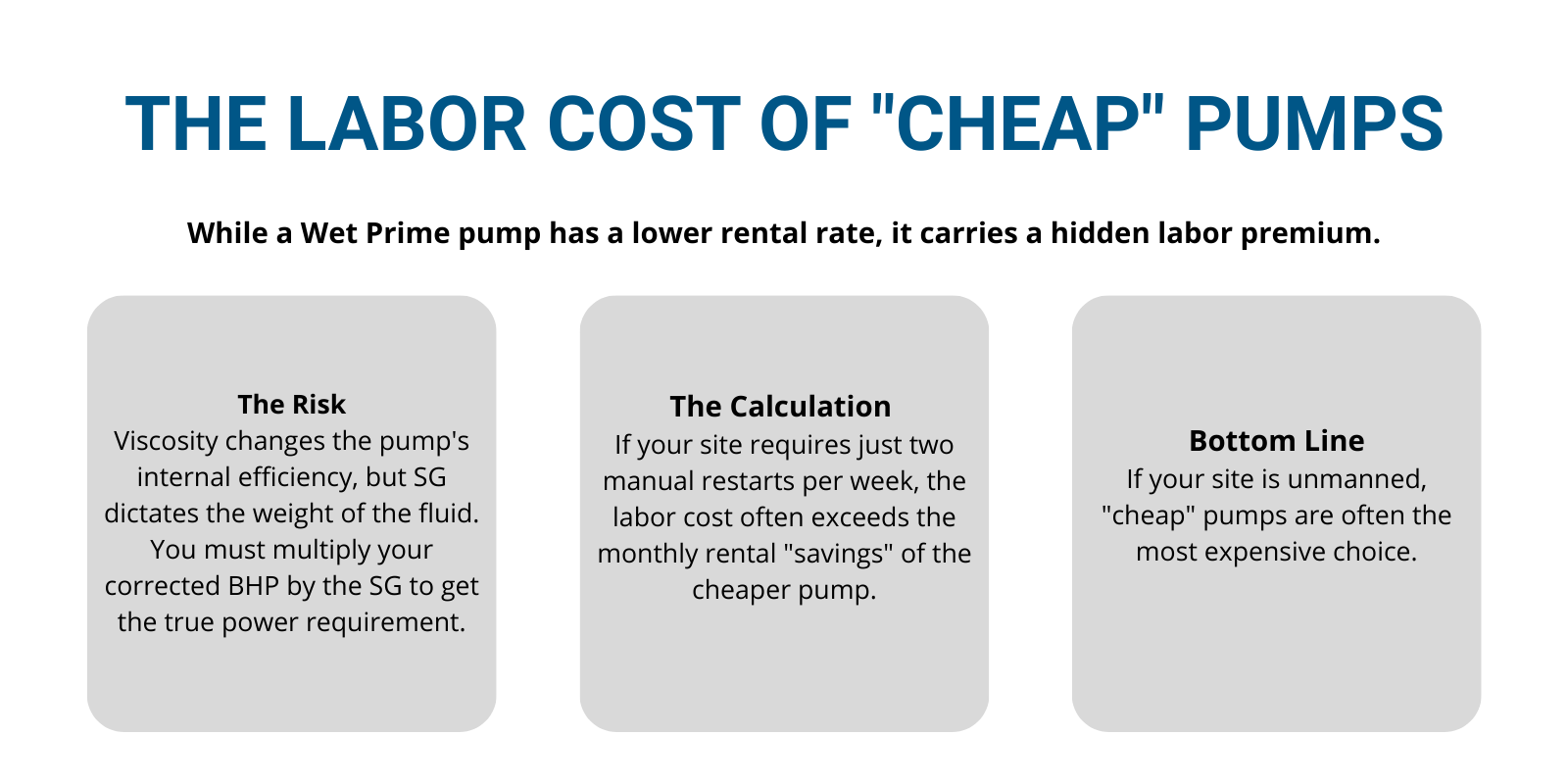

Rental Cost Analysis: When to Pay for the Upgrade

Rental decisions are rarely about pump physics alone. They are about total cost under uncertainty: downtime, callouts, fuel, and repair exposure.

Dry prime units often rent at a premium because you are renting a pump plus a vacuum priming system and typically heavier-duty seal protection. Wet prime units rent for less because the package is simpler.

To decide when to pay for the upgrade, compare the premium to the cost of even one meaningful interruption. A single prime-loss event on a bypass can trigger labor, standby equipment, and schedule impacts that dwarf the rate difference.

A practical way to frame it is to treat dry prime as a reliability add-on that may reduce hidden costs:

- Crew time: fewer manual priming interventions and fewer restarts

- Downtime risk: automatic repriming and higher tolerance of suction air

- Repair exposure: reduced seal failures from dry running

- Fuel and runtime efficiency: often better hydraulic efficiency on larger prime-assist packages, depending on the specific models and duty point

Here is a simple cost lens you can use in bid planning or fleet allocation meetings.

| Cost Driver | Wet Prime Tendency | Dry Prime Tendency |

| Daily/weekly rental rate | Lower | Higher |

| Unattended operation | Higher risk | Lower risk |

| Response labor | More likely | Less likely |

| Seal failure exposure | Higher | Lower |

| Best economic fit | Short duration, stable inflow | Long duration, variable inflow, critical uptime |

If your job is budget-driven and conditions are stable, wet prime can be the right call. If your job is schedule-driven or consequence-driven, dry prime is often cheaper after you account for operational risk.

FAQs

1. What is the main difference between wet prime and dry prime pumps?

Wet prime relies on water retained in the casing to create vacuum, while dry prime uses a vacuum-assisted system to evacuate air and can prime from dry.

2. Does a dry prime pump need water added to the casing to start?

No. A dry prime pump is designed to prime from a dry state without manually filling the casing.

3. What does “snoring” mean in dewatering pumps?

Snoring is when the pump intermittently ingests air as the water level drops and returns, creating an air-water mixture that tests priming stability.

4. Can a wet prime pump run dry without damage?

Typically no. Running dry can overheat the mechanical seal quickly and lead to seal failure.

5. Why are dry prime pumps more expensive to rent?

They include added components like a vacuum pump, priming chamber, and controls, and they often include run-dry protection features.

6. How does a vacuum-assisted priming system work?

It removes air from the suction line and pump casing using a vacuum pump or venturi priming device until water is lifted into the pump and flow stabilizes.

7. Which pump type is better for wellpoint dewatering?

Dry prime is usually better because wellpoint headers commonly carry air and require strong automatic repriming.

8. What happens if a wet prime pump loses its prime?

It stops pumping effectively and usually needs manual intervention to refill the casing and restore prime.

9. Do dry prime pumps require more maintenance?

They often require more maintenance on the priming system components, even though they may reduce field interventions tied to prime loss.

10. Can I use a wet prime pump for sewer bypass?

You can, but it is generally risky when flow varies or uptime is critical; dry prime is commonly chosen to reduce prime-loss interruptions.